Plantar Fasciitis, Heel Spurs and Cortisone Injections

What could be causing my sore heel?

What could be causing my sore heel?

Plantar fascia is a thick fibrous band of connective tissue originating on the bottom surface of the heel bone and extending along the sole of the foot towards the toes. It acts as a passive limitation to the over-flattening of your arch.

Plantar heel pain accounts for approximately 11-15% of all foot symptoms requiring medical attention in adults and for 8-10% of all running-related injuries. (Rasenberg et al, 2018)

What is it?

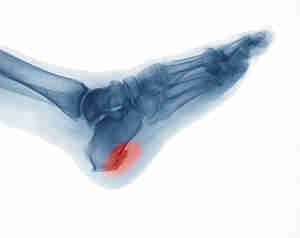

Plantar fasciopathy (previously known as ‘Plantar Fasciitis’) is an overuse condition at the point where the band of fascia attaches to the calcaneus (heel bone). People typically first notice pain under their heel or in their foot arch in the morning or after resting.

Why is it called fasciopathy now instead of plantar fasciitis?

The term “itis” means inflammation. On ultrasounds and MRI, thickening and degenerative tissue findings of the fascia are more commonly seen than inflammatory changes. “opathy” Simply means pathology (or problem) of the tendon so “fasciopathy” has become the more correct term.

Who is affected?

Heel pain commonly affects very physically active people (e.g. runners) or people with high amounts of standing occupational work (who may also have a high BMI). 1 in 10 people will suffer from plantar fasciopathy in their lifetime.

Are Heel Spur’s causing my pain?

A heel spur is a calcium deposit causing a bony protrusion on the underside of the heel bone. They are very common in people WITHOUT heel pain and there is a very poor correlation between spurs and pain. If you have been diagnosed with a heel spur it is unlikely to be causing your pain. It is very likely to be plantar fasciopathy due to its location (attaching under the heel).

How do we diagnose it?

The most important part of the diagnosis is the history. Patient’s will report a gradual onset of heel pain that it worse in the mornings when getting out of bed (“first-step pain”) and then warms up with activity. It may then return as an ache post-activity of after sitting long periods.

There is pain or tenderness along the medial/dorsal aspect (inside/underneath) of the heel bone, which may extend along the medial and central components of the plantar fascia. Stretching the plantar fascia via lifting the big toe up (during the windlass test) may reproduce pain and may assist with palpation of the plantar fascia.

Do I need to get a scan?

X-rays and MRI’s are not indicated if there is a classic history and examination findings.

What are some other possible causes of heel pain?

Bruised heel (Fat pad contusion):

A bruised heel is an injury to the fat pad that protects the heel bone. It can occur acutely and chronically due to poor heel cushioning or repetitive stops, starts and changes in direction. Pain is felt laterally in the heel during weight-bearing activities due to the pattern of heel strike. Tenderness is felt in the posterolateral heel region. This activity helps with differentiating fat pad contusion with plantar fasciopathy.

Calcaneal stress fracture:

Occurs in runners, ballet dancers and jumping athletes. History of insidious onset of heel pain that is aggravated by weight-bearing activities, especially running. Presenting with localised tenderness over the medial or lateral aspects of the heel bone. Pain is reproduced by squeezing the posterior aspect of the calcaneus (heel bone) from both sides simultaneously.

Nerve pain:

This condition presents with rear foot pain caused by entrapment of the first branch of the lateral plantar nerve. Pain radiates to the medial inferior aspect of the heel proximally into the medial ankle region. Patients do not normally complain of numbness in the heel or foot. Often confused with plantar fasciopathy, the two conditions were shown to coexist in 52% of patients with this nerve entrapment. There is maximal tenderness at the plantar medial heel just proximal to the plantar fascia.

Midfoot pain:

Acute midfoot pain results from a sprain of the mid tarsal joint or plantar fascia. Gradual pain is a sign of overuse injury such as extensor tendinopathy, tibialis posterior tendinopathy or navicular stress fracture (pain poorly localised).

Other:

Blood tests may be warranted to rule out inflammatory arthritis, which can cause symptoms in the heels (although frequently symptoms will be more widespread). Plain radiographs (lateral view) are used to investigate the presence of a ‘calcaneal spur’. MRI is useful for identifying stress fractures of the calcaneus and other soft tissue pathologies; soft tissue tumours, medial tendinopathy and plantar fat pad pathology.

How do I treat plantar fasciopathy?

Research shows the best long term relief of heel pain is strength training. (Almubarak et al., 2012)

The 2 best strength exercises:

1. Intrinsic foot muscles:

Begin sitting with your feet flat on the ground. Raise your arch by curling the big toe towards your heel, without curling your toes or lifting your heel.

2. Calf raises:

High load strength training consisting of heel-raises with a tight band around your ankles. Progress by performing on one leg at a time or by placing a towel under the toes.

What can I do for short-term relief?

The best short term relief of heel pain includes stretching and corticosteroid injections. (Babatunde et al., 2018)

The 3 best Stretching/flexibility exercises:

1. Big toe extension with ankle dorsiflexion:

Holding the big toe into slight extension and bringing the foot back into dorsiflexion.

2. Calf stretch:

Standing with your hands leaning against a wall for support and place the affected leg behind. Keep the leg straight and slight lean forward at the ankle joint. Feeling the gentle stretch in the calf muscle.

3. Self-massage with a golf ball:

Place a golf ball under the bottom of your foot and gently roll the ball back and forth.

Do Corticosteroid injections work?

Corticosteroid injections, alone or in combination with exercise were ranked most likely to be effective for management of short-term pain and function in the ‘Comparative effectiveness of treatment options for plantar heel pain’ study. However, in the long term, only exercise was beneficial.

What doesn’t work?

- Heat/ice pack

- Massage

- Orthotics

- Interferential

- Ultrasound

- Acupuncture

These options provide short term pain relief of up to 2-3 hours post treatment and are not as effective as exercise therapy. Interventions such as exercise (strength and flexibility) provide excellent long term benefits and pain relief solutions for plantar fasciopathy.

Foot orthoses vs Stretching

A systematic review and meta-analysis in the ‘Efficacy of foot orthoses for the treatment of plantar heel pain,’ explores the effect of different foot orthoses versus stretching exercises (Achilles and plantar fascia). The study showed that foot orthosis interventions are not superior in improving pain, function or self-reported recovery when compared with other conservative interventions in patients with plantar heel pain.

Orthotics vs Exercise therapy

The systematic review of ‘Exercise Therapy for Plantar Heel Pain,’ discussed the effect of exercise therapy versus the combination of customised orthotic devices and exercise. The trial concluded that both exercise therapy and combination of exercise with a customised orthotic device reduced the overall foot pain when compared with baseline results. However, the exercise therapy alone group was more effective in reducing overall pain than the combination group in those who stood for 8 hours or more daily.

The findings of this review support the use of exercise therapy following acute and chronic plantar heel pain over control/sham therapy, repetitive shock wave therapy, NSAIDs and orthotic devices.

References

Almubarak, A., & Foster, N. (2012). Exercise Therapy for Plantar Heel Pain: A Systematic Review[Ebook].

Babatunde, O., Legha, A., Littlewood, C., Chesterton, L., Thomas, M., & Menz, H. et al. (2018). Comparative effectiveness of treatment options for plantar heel pain: a systematic review with network meta-analysis. British Journal Of Sports Medicine, 53(3), 182-194. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2017-098998

Brukner, P., Clarsen, B., Cook, J., Cools, A., Crossley, K., & Hutchinson, M. et al. (2017). Clinical Sports Medicine (5th ed.).

Rasenberg, N., Riel, H., Rathleff, M., Bierma-Zeinstra, S., & van Middelkoop, M. (2018). Efficacy of foot orthoses for the treatment of plantar heel pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. British Journal Of Sports Medicine, 52(16), 1040-1046. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2017-097892